Myocardial Bridging: Can a New Heart Scan Predict Your Risk?

"CCTA-derived FFR offers a non-invasive way to assess the severity of myocardial bridging and its link to angina, paving the way for better diagnoses and personalized treatment."

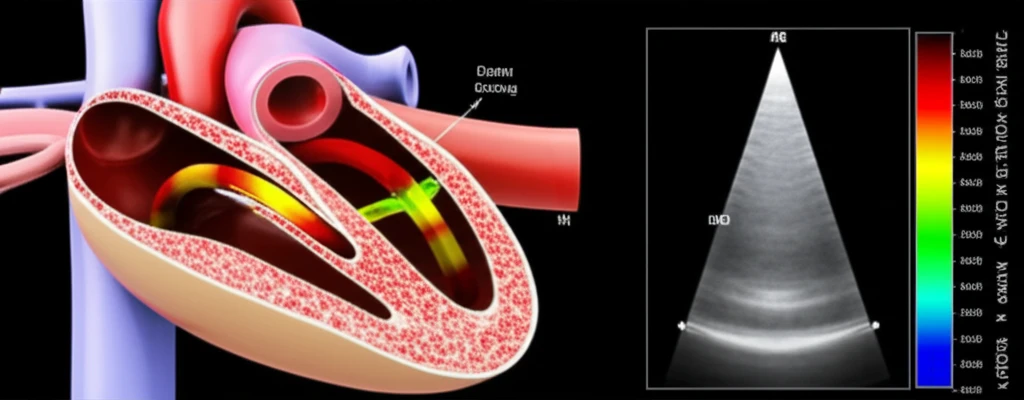

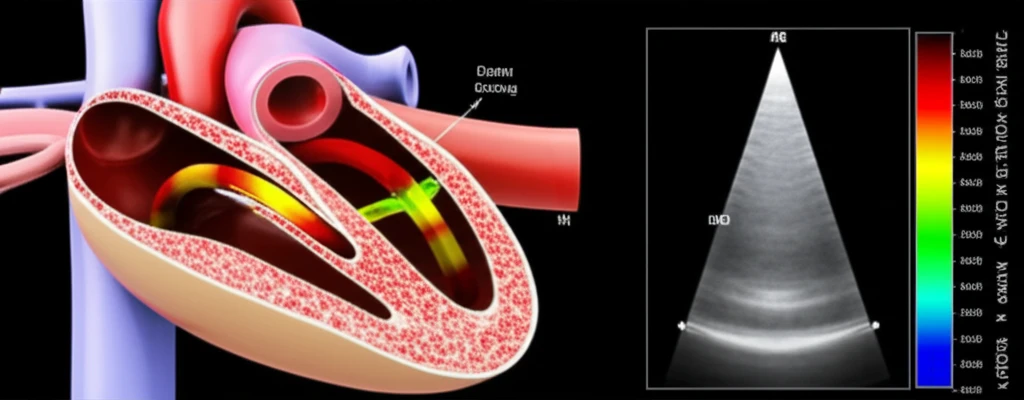

Myocardial bridging (MB), where a segment of a coronary artery travels through the heart muscle instead of lying on its surface, is often considered a harmless quirk of anatomy. However, for some, it can lead to chest pain (angina) and other concerning symptoms. Determining who is at risk and how best to manage their condition has been a challenge for cardiologists.

Traditional methods like standard CT scans can visualize the bridge itself, but struggle to assess how much it's impacting blood flow to the heart. This is where a new approach using CCTA (coronary computed tomography angiography)-derived fractional flow reserve (cFFR) comes in. CCTA is a non-invasive heart scan that uses CT technology to create detailed 3D images of the coronary arteries, and can help determine which patients may benefit from further invasive testing.

This article explores how cFFR, calculated from standard CCTA scans, could help doctors better understand the significance of myocardial bridging, predict which patients are likely to experience symptoms like angina, and ultimately guide treatment decisions. We'll break down the research findings, what they mean for you, and why this non-invasive approach could be a game-changer in cardiac care.

CCTA-Derived FFR: A New Way to Assess Myocardial Bridging

Researchers sought to evaluate whether cFFR, derived from routine CCTA scans, could effectively assess the impact of MB on blood flow and identify factors associated with significant flow abnormalities. The study compared cFFR values in patients with MB to those without, examining relationships between cFFR, anatomical features of the MB, and the presence of chest pain.

- Lower Blood Flow: Patients with MB had lower cFFR values in the bridged segment and in the artery segment beyond the bridge, compared to individuals without MB. This suggests that MB can indeed affect blood flow.

- Depth Matters: cFFR differences were more pronounced during systole (when the heart muscle contracts) in those with deeper MBs (where the artery is buried further within the heart muscle).

- Bridge Length and Squeezing: The length of the MB and the degree of artery squeezing (systolic stenosis) were key predictors of abnormal cFFR values. Longer bridges and greater squeezing were linked to more significant flow disturbances.

- Angina Connection: MB patients with abnormal cFFR values were more likely to experience typical angina symptoms.

The Future of MB Assessment: Personalization and Prevention

This research indicates that cFFR holds promise as a non-invasive tool to assess the functional significance of myocardial bridging. By identifying patients with MB who are more likely to experience flow disturbances and angina, cFFR could help guide treatment decisions, potentially avoiding unnecessary invasive procedures in those with mild or insignificant bridging.

While these findings are promising, further research is needed to determine the long-term prognostic value of cFFR in MB patients and to compare its accuracy against other diagnostic methods. Studies tracking patients over time, correlating cFFR values with clinical outcomes, will be crucial to validate its role in clinical practice.

The application of cFFR for MB is another step towards personalized medicine, where treatments are tailored to an individual's unique anatomy and physiology. By combining detailed imaging with functional assessment, doctors can move beyond simply identifying the presence of MB to understanding its true impact on each patient's heart health.